A Popular Way to Experience Japanese Cuisine Easily

What Is Conveyor Belt Sushi?

Conveyor belt sushi is a casual and enjoyable way to experience Japan’s sushi culture. Unlike traditional sushi bars where chefs prepare each piece in front of customers, conveyor belt sushi offers a more affordable and accessible option with a wide variety of dishes.

This style is loved by families, solo diners, and tourists alike for its convenience and fun experience.

How Conveyor Belt Sushi Works

Dishes travel around the restaurant on a rotating conveyor belt, and customers can take what they like at any time. Plate colors usually indicate price, and the total cost is calculated by counting plates. This straightforward system and the freedom to choose at your own pace are key attractions.

- Choose what you like, as much as you like

- Clear pricing, easy to understand

- Comfortable to visit alone

- Family-friendly

Today, touchscreen ordering and high-speed lanes are common, improving efficiency and hygiene.

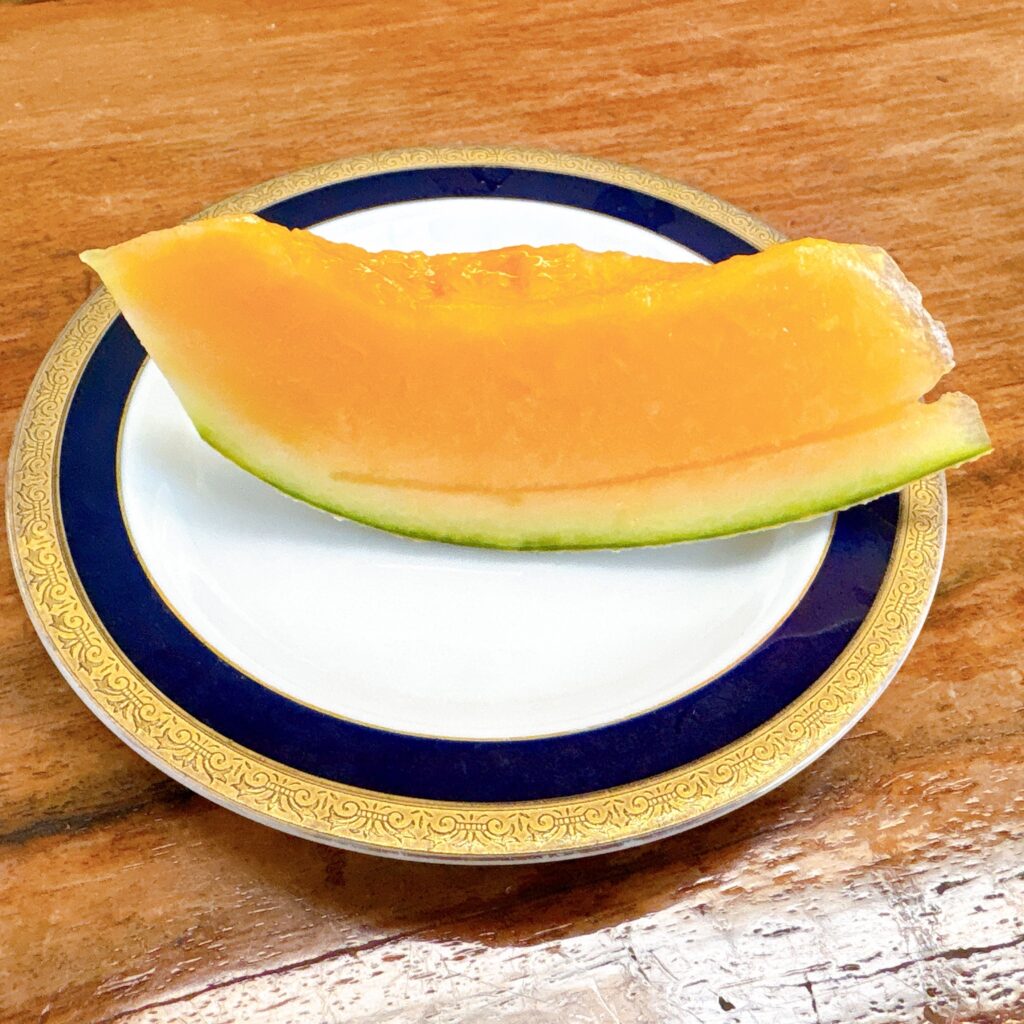

Variety of Menu Options

While traditional items like tuna and salmon are staples, many creative dishes have been introduced in recent years.

- Seared sushi and cheese-topped creations

- Tempura sushi and roast-beef sushi

- Side dishes like udon, ramen, and fried chicken

- Desserts such as pudding and ice cream

Even those who don’t prefer raw fish can enjoy the experience thanks to the diverse menu.

Popular Conveyor Belt Sushi Chains

Japan has several famous conveyor belt sushi chains, each with its own unique style. Trying different ones during your trip can be a fun adventure.

- Sushiro

- Kura Sushi

- Hama Sushi

- Kappa Sushi

Many chains offer seasonal menus, promotions, and exclusive items.

Basic Etiquette

Although the atmosphere is casual, there are a few manners to keep in mind:

- Do not return plates once taken

- Take only items ordered for your seat

- Do not place personal items on the conveyor

These help everyone enjoy the experience comfortably.

Conclusion

Conveyor belt sushi is a uniquely Japanese dining style that blends tradition with modern convenience. With affordable prices, diverse menus, and a relaxed atmosphere, it has become a beloved part of daily life in Japan.

When visiting, try both the classic sushi offerings and the restaurant’s original creative dishes. Enjoy the convenience and fun — and discover your new favorite sushi!